A Brief History of Egyptian Belly Dance and the Women Who Found Power in Performance

By Kenzy Fahmy

The idea of finding freedom in dance is neither new nor unusual, freedom of spirit, of expression. Dance allows us to shed the restraints of reality and of the social customs that bind us. It brings people together through an ancient language that we all instinctively know and understand. But seldom do we talk about the independence and social freedoms that dance has afforded women for centuries. For many women, a career in entertainment was their ticket out of poverty, and very often, it was their way out of unhappy or abusive marriages, of a life lived within the constraints of what society deemed acceptable for them.

The origins of raqs baladi (folk dance) or sharqi (eastern), belly dance in English – from the French danse du ventre, are still the subject of debate, but the practice goes back at least a few hundred years and can be found in historical descriptions across the region. Ancient Egyptian temples often show women dancing to appeal to the gods and pray for gifts of love and fertility. It was an important rite of passage into womanhood and a powerful expression of divine femininity.

Several hundred years later, during the 18th and 19th century, the dance evolved into a form of entertainment performed by women called the Awalim and the Ghawazee, women who were in many ways a class of their own. Awalim were similar to courtesans; they were well educated and often came from good families and social backgrounds, trained at a young age to sing, recite poetry and dance at important events in cities throughout the country.

Ghawazee on the other hand were often lower class women who were uneducated and relied on dancing as a source of income. They didn’t receive the same training as the Awalim, they were the more traditional folk dancers, performing usually in more informal and rural settings, singing in the Upper Egyptian dialect and wearing costumes that were the same as those worn by the local farming communities. Although the two terms represent two distinct types of performer, in reality there was a lot of overlap between the two, and the terms were often used interchangeably.

It was during the 1800s that the Awalim and Ghawazee began to form their own independent careers. The dancers were making a name for themselves and carving a brand new path for women in Egypt. Women like Kuchuk Hanem, Bamba Kashar, Shok and Shafiqa al-Qibteya were starting to gain the recognition of both local and international audiences, sometimes even performing at expos in Europe and America. The dancers were described in various accounts and descriptions of Egypt and were featured in countless Orientalist paintings, drawing in audiences from around the world who came to watch the exotic performances; the colonial gaze however saw them as objects, as oppressed women, and not as the empowered women they were.

The women found not only independence in their ability to make a living, but also power and influence in their expanding circles that included some of the country’s most important figures, from celebrities to politicians. And they didn’t shy away from using either. Women like Shafiqa were extremely active politically, playing important roles in the fight for independence from Britain and the rise of the new nationalist opposition. Many of them were spies, and like Mata Hari, they were called on to use their influence to extract information from the men they performed for.

Badia Massabni - Image Credit

In 1926, Badia Massabni, “The Godmother of Belly Dance”, opened her own night club, Salet Badia, ushering in a new era of dance and performing arts in Egypt; this was the birth of the Egyptian cabaret and the start of Egypt’s “Golden Era” of entertainment. The dance halls of Azbakeya were being replaced by more upscale cabarets on Emad El Din Street in Downtown Cairo, the city’s newest up-and-coming neighbourhood. Massabni was reinterpreting the traditional folk dance and began to introduce Western music and dance styles like ballet. She also introduced the two-piece dance costume we still see in use today. It was Badia’s clubs that launched the careers of musicians like Mohamed Fawzi, Mohamed el Kassabgi and Riad el Sunbati.

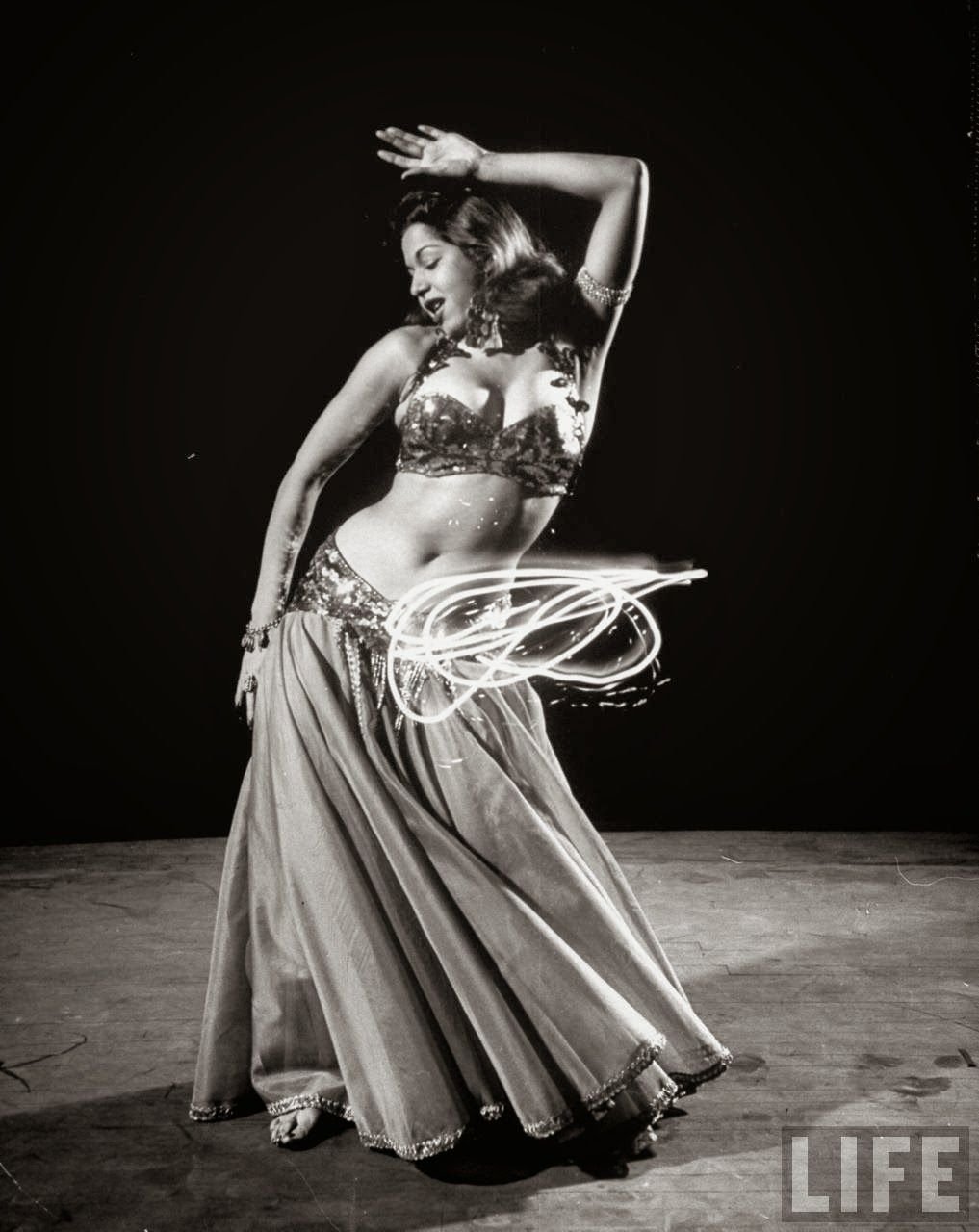

Samia Gamal performing in the US - Image Credit

The club also served as a dance academy and it was here that Tahiya Carioca and Samia Gamal, two of Egypt’s most iconic dancers, found their calling. Carioca and Gamal took Egyptian belly dance to dizzying new heights of popularity, appearing regularly in films, along with Naima Akef, and starring opposite actors and singers like Farid al-Atrash and Roshdi Abaza, who Gamal would later marry, and divorce. They lived tumultuous lives, both in private and in public, but they both left their own eternal mark, not only on the art form itself, but in the hearts of all who have watched them dance.

The 60s saw a new generation of dancers grace the stage and screen. Women like Nagwa Fouad, who had an impressive 45-year career and starred in dozens of films, and Soher Zaki, who Sadat called the “Um Kalthoum of Dance”. But the 60s were also a time of intense socialist and nationalist ideologies, and the cabarets, along with their belly dancers, were being left behind in favour of more traditional folk dancing. But the belly dancers were quick to pick up on the trend, adjusting their styles and costumes to fit the world’s ever-changing tastes.

Fifi Abdou - Image Credit

The next few decades brought yet another generation of performers, as well as a brand new audience. More and more tourists were coming in from the Gulf and Haram Street replaced downtown as Cairo’s nightlife hub. Fifi Abdo, a legend in her own right, started dancing at 13, and rose to the position of Egypt’s most famous dancer during the 80s and 90s. She is now one of the country’s wealthiest women, loved by all regardless of views or beliefs. Abdo, with her unapologetically loud personality and incredibly strong character, was able to rise above the stigma and demand the respect of society despite working in a profession that remains as controversial as ever.

Dance has empowered more than one generation of Egyptian women, freeing them from the chains imposed by traditional gender roles and offering power and independence that would otherwise have been inaccessible to them. Rulers have come and gone, and many have tried to banish the ancient practice, but none have succeeded. It has allowed women who came from poor and illiterate households to mingle with the uppermost rungs of society, to see the world and to play an active role in both their own lives and the lives of those around them. It gave women the knowledge and resources to teach and support each other as they too danced their way out of poverty and oppression. Their lives may not have been easy, but at least they were free.