The City of the Dead: Cairo’s Historic Necropolis

Kenzy Fahmy

For centuries, the residents of Cairo, both rich and poor, have been laid to rest within the tombs and mausolea that make up the aptly named City of the Dead, for it is a city, but it is inhabited by the living as much as the dead. In this sprawling necropolis, one of the largest in the world, life and death exist side by side in the kind of harmony you can find only in places like these. This deep-rooted relationship between life and death, between this world and the next, goes all the way back to our ancient ancestors. Even our tombs are a remnant of ancient Egyptian burial practices.

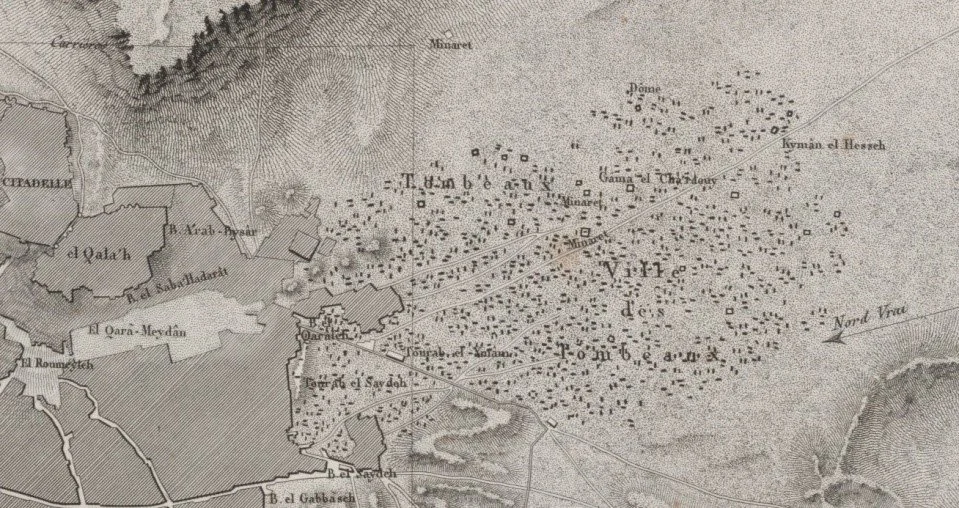

Cairo’s City of the Dead, known locally as al-Qarafa, a general term used for the city’s cemeteries, has existed for almost 1400 years, its origins dating back to the 7th century Islamic conquest of Egypt, led by Amr ibn al-‘As, and the foundation of the city of Fustat. The land was divided into plots that were then allocated to different Arab tribes who each built their own cemetery; it is said that the name “Qarafa” actually comes from an ancient Yemeni clan that once inhabited the land.

As the city grew and evolved, administrative capitals shifted from neighbourhood to neighbourhood and the cemeteries expanded and shifted along with them. Under the Abbasids and Ibn Tulun, the necropolis inched its way north towards al-‘Askar and al-Qata’i neighbourhoods where the Citadel and the Mosque of Ibn Tulun now stand. By the 10th century, the cemeteries had grown so vast that they reached all the way south to where Basatin is today.

It was around this time that the Fatimid dynasty revived the tradition of building mausoleums and extravagant above-ground tombs. Mosques and madrassas were built alongside the tombs, as well as a number of great palaces and homes; the cemeteries were becoming cities in their own right. This is also when we started to see people residing within the necropolis, including workers who operated and maintaned the the schools, mosques and tombs, as well as scholars and Sufis who attended the madrassas.

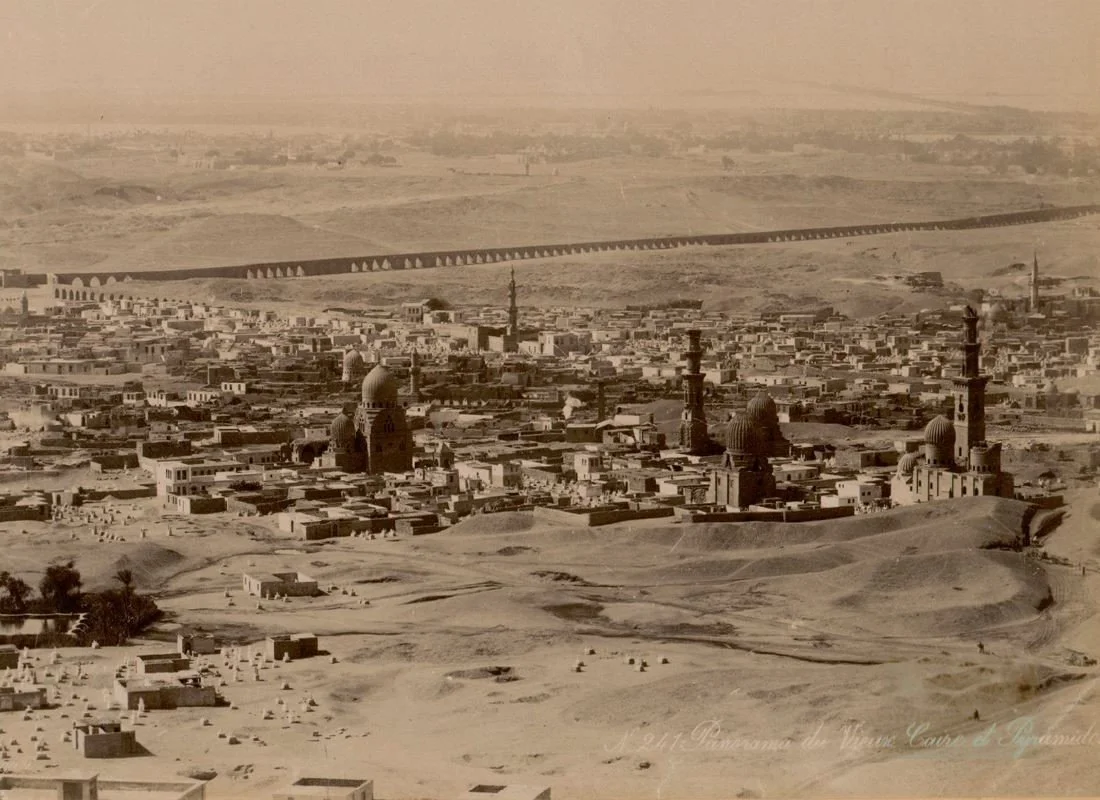

The Mamluks led a new wave of development during the 13th and 14th centuries, establishing a new cemetery south of the Citadel, an area known as saharet el mamaleek (desert of the Mamluks), and another to the north. A number of Mamluki sultans had stunning domed mausoleums built for themselves and the funerary complex of Sultan Qaybay is among the most famous and most spectacular. Here again we saw the tradition of building schools and Sufi khanqahs (gathering spaces) alongside the tombs and the population of the necropolis grew to an estimated four thousand people. The Mamluks oversaw a period of significant expansion and wealth in Egypt, and the City of the Dead mirrored this in every way, especially in its architecture.

Fast forward to the 19th century, the French have come and gone, and Ottoman rule had just come to an end. Mohamed Ali established his own ruling dynasty in the very early 1800s and put into action his mission to modernize Egypt. One of the many changes he made was to limit the use of the cemeteries to burial practices; he wanted to discourage people from residing there. He even interfered with the trusts that had been set up to pay for the upkeep of the tombs and mausolea and began taxing them. But this didn’t last long, and after he himself was buried in an impressive mausoleum next to al Imam al Shafie, another hugely iconic tomb, he triggered a new trend that saw the country’s elite construct their own lavish tombs and complexes which required the presence of workers to keep them maintained and serviced. By the late 1800s the population of the cemeteries and their surrounding neighbourhoods had reached over 30,000 residents.

Over a thousand years after its inception and the historic cemeteries remain an important part of Cairo’s identity. They now cover an area of almost twelve kilometers, rippling out from the Citadel to make up a Northern and a Southern cemetery. What used to be distinct areas now merge seamlessly with one another and with the city at large. The City of the Dead is also a city for the living, with thousands of families calling the necropolis home, from those who have been managing the tombs for generations, to those who simply needed shelter.

While it might be difficult to ignore the morbidness that might normally surround the idea of living amongst the dead, residents of al-Qarafa have formed a close-knit and very supportive community. They’ve found peace and safety within the walls of the necropolis and most of them wouldn’t think of leaving this behind. Walking through the alleys of the city, along dusty paths and past beautiful old doors carrying the names of those who lay buried inside, a sense of calm permeates the air. Life is slower here, quieter. Past and present exist as one and time seems to no longer exist, the world outside seems to no longer exist. The residents of the City of the Dead are happy, probably more so than the rest of Cairo. They managed to find a place for themselves in a world that is becoming more challenging by the day.

The centuries old necropolis was finally listed as a UNESCO world heritage site in 1979. Recently, plans to build a new bridge have posed a threat to the incredible heritage that the city holds. A number of tombs have already been demolished and there are plans to demolish more. Thankfully, a number of people of organizations have stepped forward and are making great efforts to preserve what remains, be it in the form of petitions and awareness campaigns, or in the form of projects that aim to document and record as much as possible. Walking tours like those organized by Walk Like an Egyptian are becoming increasingly popular as more and more people shine a spotlight on the tangible and intangible value of the necropolis and the importance of protecting it.